Awareness Without Permission: Why MAGA Can Recognize Authoritarianism but Cannot Apply It to Itself

A psychological account of projection, loyalty, and moral insulation in an authoritarian movement

I. Recognition Without Self-Application:

What MAGA Sees And Why That’s Not Insight

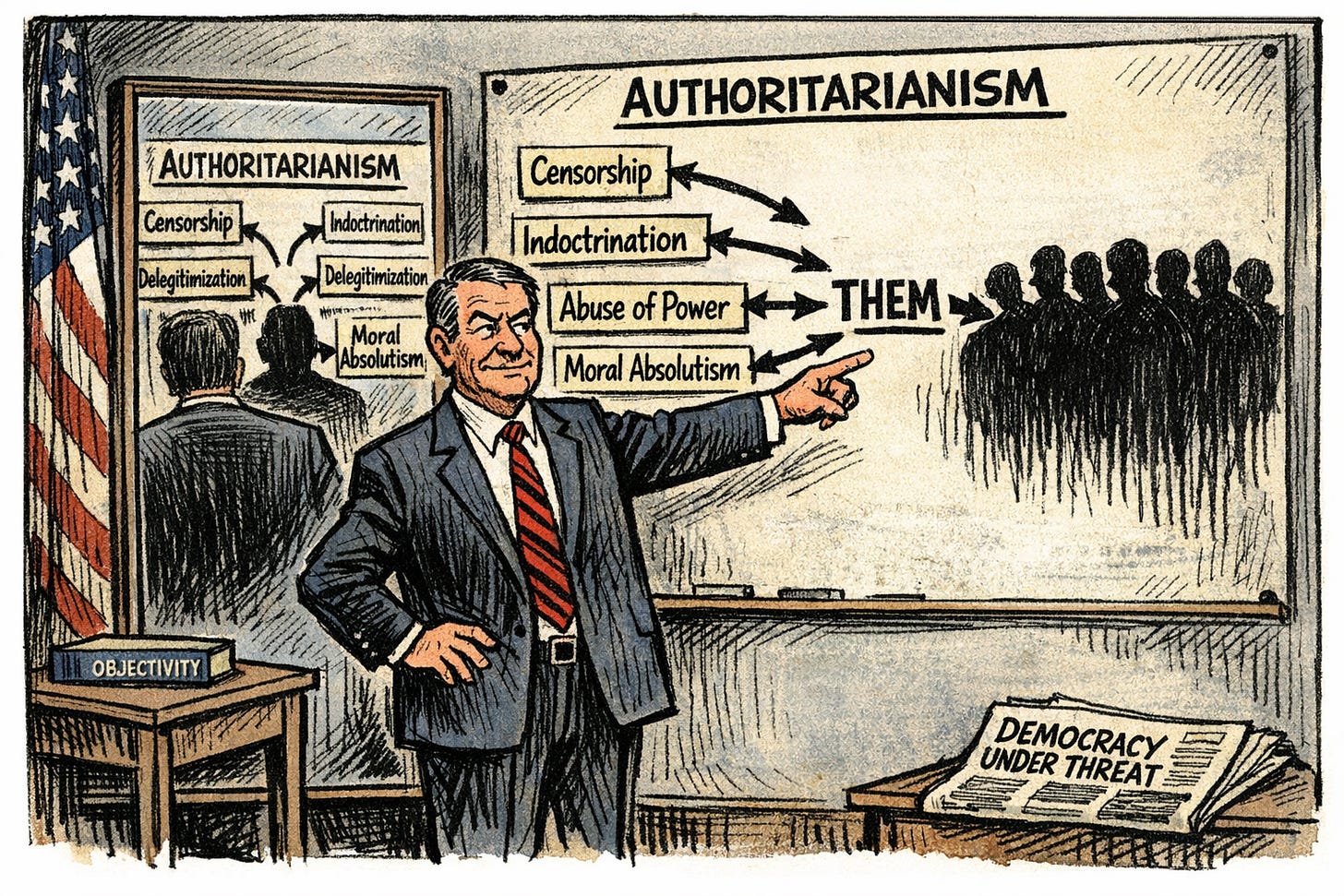

One of the more misleading assumptions in contemporary political debate is that authoritarian movements persist because their supporters fail to recognize authoritarian behavior. The evidence suggests something more complicated, and more unsettling. Authoritarian-aligned voters are often quite capable of identifying authoritarian structures when those structures are perceived to exist elsewhere. They can name censorship, indoctrination, delegitimization, and persecution with real fluency. What they struggle to do is apply those same recognitions inward, to their own group, leaders, or actions. This is not a deficit of awareness. It is a failure of self-application.

The distinction matters. Recognizing a pattern does not require moral risk. Applying it to oneself does. Psychological research has long shown that individuals evaluate behavior differently depending on whether it is attributed to an outgroup or to the self. Jones and Nisbett’s work on the actor–observer asymmetry demonstrated that people tend to explain others’ actions in dispositional terms while interpreting their own behavior as situational and justified by context. When applied to political identity, this asymmetry produces a predictable distortion: outgroup actions are read as evidence of character and intent, while ingroup actions are explained as reactive, constrained, or necessary responses to provocation (Jones & Nisbett, 1971).

This dynamic allows authoritarian mechanisms to be recognized structurally but mislocated psychologically. When censorship is attributed to an opposing political camp, it appears as evidence of ideological repression. When similar restrictions are enacted by one’s own side, they are reframed as protection, regulation, or common sense. The same mechanism applies to accusations of indoctrination, moral absolutism, or abuse of power. The structure is seen. The source is displaced.

The bias blind spot compounds this asymmetry. Pronin and colleagues demonstrated that individuals reliably perceive cognitive biases in others while denying those same biases in themselves, even when explicitly informed about the bias in question. Importantly, this is not because people believe themselves superior thinkers in the abstract, but because introspection feels subjectively neutral. People trust their own reasoning precisely because it feels unmotivated from the inside, even when it is not (Pronin et al., 2002). This produces a dangerous illusion in political contexts: the belief that one’s conclusions are evidence-based while opponents are driven by ideology, emotion, or bad faith.

Once political identity becomes central to self-concept, this illusion hardens. Research on identity-protective cognition shows that individuals selectively accept or reject information based on whether it threatens the status of their cultural or political group. Kahan’s work demonstrates that higher cognitive sophistication does not reduce this effect; in many cases it intensifies it, allowing individuals to defend identity-consistent beliefs with greater argumentative skill. Reasoning is recruited not to discover truth, but to preserve belonging and moral coherence (Kahan et al., 2007). Under these conditions, recognizing authoritarian behavior in one’s own group would require more than intellectual acknowledgment. It would require risking social identity.

This helps explain why accusations directed outward can be precise without being reflective. The mind is capable of identifying authoritarian traits in the abstract while remaining functionally blind to their presence in familiar forms. Authoritarianism is imagined as something crude, obvious, and external: jackboots, overt repression, foreign regimes. When similar mechanisms appear domestically, embedded in language about safety, order, tradition, or protection, they do not register as authoritarian at all. The pattern has been recognized, but it has been cognitively walled off from self-application.

Biased assimilation further entrenches this divide. Lord, Ross, and Lepper showed that individuals exposed to mixed evidence on contested political issues do not converge toward moderation. Instead, they selectively credit information that supports prior beliefs and scrutinize opposing evidence more harshly, often becoming more polarized as a result. This process reinforces the sense that one’s own side is responding rationally to reality while the other is engaged in distortion or manipulation (Lord et al., 1979). When applied to accusations of authoritarianism, the result is predictable: evidence of outgroup misconduct is absorbed as confirmation, while evidence of ingroup misconduct is reframed as exaggerated, contextless, or maliciously motivated.

Group loyalty intensifies this effect. Cohen’s research on party influence demonstrated that individuals routinely abandon policy preferences when those preferences conflict with the stated position of their political group. What appears as ideological consistency is often group alignment masquerading as principle. In this environment, self-scrutiny becomes socially costly. To acknowledge that one’s own group is engaging in authoritarian behavior is not merely to revise an opinion, but to risk exclusion from the group that confers identity and moral standing (Cohen, 2003).

Taken together, these findings point to a consistent conclusion. The inability to apply authoritarian critiques inward is not the result of ignorance, irrationality, or lack of exposure to information. It is the predictable outcome of cognitive asymmetries that favor outgroup scrutiny and ingroup protection. People do not fail to see the mechanisms. They fail to see themselves as capable of enacting them. Recognition remains intact. Self-recognition is filtered out.

This distinction is essential for understanding MAGA’s rhetorical posture. The movement’s accusations often display a sharp grasp of authoritarian structure while remaining insulated from self-implication. The mirror works, but only when it is pointed outward. What follows in later sections is not a breakdown of awareness, but a defense of identity.

II. Projection as Psychological Defense (Not Strategy): Why Accurate Accusations Are Misassigned

Projection is often misunderstood as a rhetorical maneuver, something deployed deliberately to confuse, manipulate, or evade accountability. The psychological literature tells a less theatrical and more consequential story. Projection is not primarily a strategy. It is a defense. It functions to protect identity, preserve moral coherence, and relieve cognitive tension when actions or impulses threaten the self-concept. When political identity becomes morally saturated, projection does not merely misdirect blame; it stabilizes the inner narrative that allows the individual to remain certain of their own righteousness.

Classical psychoanalytic theory introduced projection as a mechanism through which unacceptable impulses are attributed to others in order to avoid internal conflict. While the language of early theory has evolved, the core insight remains intact in modern social psychology. When individuals encounter evidence that implicates their own group in morally troubling behavior, acknowledging that evidence would require revising self-understanding. Projection offers a less costly alternative. The troubling behavior is recognized, but reassigned. The discomfort is relieved without requiring moral revision.

This mechanism helps explain a recurring feature of contemporary political discourse: the precision of certain accusations paired with their persistent misdirection. Accusations of censorship, indoctrination, authoritarianism, or persecution often mirror the structure of behaviors enacted by the accuser’s own side. The resemblance is not coincidental. The structure has been cognitively registered. What is displaced is ownership.

The bias blind spot reinforces this displacement. Pronin’s work demonstrates that people experience their own judgments as objective and unmotivated, while perceiving others as driven by bias, ideology, or emotion. This asymmetry is not resolved by awareness of bias; it survives instruction and reflection because introspection itself feels transparent. Individuals trust their conclusions because they experience them as reasoned, even when those conclusions serve identity-protective ends (Pronin et al., 2002). In political contexts, this allows projection to feel sincere. The individual does not experience themselves as projecting. They experience themselves as describing reality.

Once projection is activated, it often pairs with delegitimization. Bar-Tal’s work on delegitimization describes how groups deny the moral standing of an outgroup by characterizing it as dangerous, corrupt, irrational, or subhuman. Delegitimization does not merely criticize behavior; it reclassifies the actor. When projection assigns authoritarian intent to an opposing group, delegitimization supplies the moral justification for treating that group as an illegitimate participant in democratic life (Bar-Tal, 1989). The accusation does double work. It absolves the ingroup while licensing exclusion of the outgroup.

This process is amplified in environments of perceived threat. Lifton’s analysis of totalist systems showed how ideological movements under stress narrow acceptable thought, elevate moral absolutism, and externalize blame to preserve internal coherence. While Lifton’s work focused on extreme cases, the underlying dynamics are broadly applicable. Under threat, ambiguity becomes intolerable. Contradictions are expelled rather than integrated. Projection allows the group to maintain a vision of itself as embattled and virtuous, even while engaging in practices it condemns elsewhere (Lifton, 1961).

Van Dijk’s work on ideology further clarifies how projection becomes embedded in discourse. Ideological narratives are structured around positive self-presentation and negative other-presentation. This is not incidental rhetoric but a foundational feature of group-based meaning-making. Actions taken by the ingroup are framed as necessary, defensive, or principled, while similar actions by the outgroup are framed as aggressive or immoral. Projection operates within this structure by assigning negative motives outward while preserving an internally consistent moral story (van Dijk, 1998).

What makes projection especially resilient is its compatibility with moral licensing. When individuals or groups view themselves as fundamentally good or as defenders of a higher moral order, they experience greater latitude to excuse actions that would otherwise provoke moral discomfort. The belief in one’s own moral mission reduces sensitivity to contradiction. Accusations directed outward reinforce this license by reaffirming the group’s role as responder rather than initiator. Harmful actions are reframed as reluctant necessities imposed by an unworthy opponent.

This is why MAGA accusations so often sound convincing even to outside observers. They are not random fabrications. They are recognitions without ownership. The mechanisms being named are real. The behaviors exist. What is missing is self-implication. Projection resolves that absence by relocating the problem elsewhere.

Understanding projection as defense rather than strategy changes how the phenomenon should be interpreted. It is not evidence of bad faith in the narrow sense. It is evidence of a psychological economy organized around identity preservation. The accusation is not designed to persuade an opponent. It is designed to stabilize the self.

The result is a political discourse in which the mirror functions only in one direction. Reflection is permitted so long as it does not become recognition. What appears as argument is often the defense itself, enacted in language.

III. Loyalty as the Organizing Value: Why Self-Reflection Becomes Dangerous

In democratic theory, loyalty is often treated as a secondary virtue, subordinate to principles such as accountability, pluralism, and the rule of law. In authoritarian psychology, that hierarchy is reversed. Loyalty becomes the organizing value around which moral reasoning is structured. Once this reversal occurs, self-reflection ceases to function as a corrective and begins to register as a threat. Insight destabilizes rather than enlightens, because it risks disrupting the moral and social order that sustains the identity.

This inversion has been documented repeatedly in the study of authoritarianism. Adorno and his collaborators described authoritarian personalities as marked by a pronounced tendency toward submission to perceived legitimate authority, coupled with moral absolutism and hostility toward deviation. What mattered most was not the content of the authority’s demands, but the preservation of order, hierarchy, and group cohesion. Moral judgment flowed downward from authority rather than upward from principle, making obedience feel virtuous in itself (Adorno et al., 1950).

Later research refined and empirically strengthened these insights. Altemeyer’s work on right-wing authoritarianism demonstrated that authoritarian followers are characterized by three interlocking tendencies: submission to established authorities, aggression sanctioned by those authorities, and adherence to conventional norms. Crucially, these tendencies do not arise from intellectual deficiency. Altemeyer found that authoritarian individuals are often capable of complex reasoning, but that reasoning is selectively applied in ways that defend authority and group norms. Questioning leaders or institutions perceived as legitimate does not feel like moral courage; it feels like betrayal (Altemeyer, 1996; Altemeyer, 2020).

This helps explain why self-critique becomes psychologically costly in authoritarian movements. To acknowledge wrongdoing by a leader or ingroup is not a neutral reassessment. It threatens the legitimacy of the authority to which loyalty has been pledged. Once loyalty is moralized, doubt becomes indistinguishable from disloyalty. Under those conditions, conscience is subordinated to cohesion, and obedience is experienced as ethical alignment rather than compliance.

Stenner’s work on the authoritarian dynamic adds an important situational dimension. Authoritarian predispositions do not operate constantly at full intensity; they are activated by perceived threat, particularly threats to normative order and group unity. When individuals perceive social change, cultural pluralism, or institutional challenge as destabilizing, they become more willing to trade tolerance for conformity and dissent for discipline. In such moments, demands for unity intensify, and deviation is treated as danger rather than disagreement (Stenner, 2005).

This dynamic clarifies why self-reflection is especially unwelcome during periods of perceived crisis. Calls for accountability or restraint are not heard as principled objections. They are interpreted as weakening the group at a moment when unity is framed as existentially necessary. The question is no longer whether an action violates democratic norms, but whether questioning it undermines collective resolve.

Hetherington and Weiler’s work on authoritarianism and polarization shows how this psychology maps onto contemporary American politics. They demonstrate that authoritarian voters are less committed to democratic procedures when those procedures produce outcomes they perceive as threatening. Support for civil liberties, institutional independence, and checks on power becomes conditional. What remains constant is loyalty to the ingroup and its leaders. Democratic norms are valued instrumentally, not intrinsically, and are readily sacrificed when they appear to conflict with group survival or dominance (Hetherington & Weiler, 2009).

Importantly, this does not imply cognitive incapacity. Research on cognitive ability and authoritarianism complicates the caricature that authoritarian followers are simply less intelligent or less informed. Higher cognitive ability does not reliably inoculate against authoritarian attitudes. In some cases, it enhances the ability to rationalize obedience and justify hierarchy. Intelligence becomes a tool for defending loyalty, not for interrogating it. Insight is redirected outward, toward the identification of enemies and threats, rather than inward toward self-examination.

Within this framework, MAGA’s resistance to self-reflection does not require invoking stupidity, ignorance, or mass delusion. It follows logically from an identity structure in which loyalty has become the primary moral axis. Once loyalty is sacralized, self-critique becomes morally suspect. To question the leader is to question the group. To question the group is to risk exclusion. Under those conditions, the safest path is not introspection but defense.

This is the psychological terrain on which projection thrives. When loyalty organizes moral life, acknowledging ingroup authoritarianism would fracture the very bonds that provide meaning and certainty. The mind resolves that tension by preserving loyalty and displacing critique. What looks like stubbornness from the outside is, from the inside, the maintenance of moral order.

The danger is not that loyalty exists. All political movements rely on some degree of solidarity. The danger arises when loyalty ceases to be conditional and becomes absolute. At that point, conscience no longer disciplines power. Power disciplines conscience.

IV. Delegitimization-by-Label: Why Naming Replaces Analysis

When political argument gives way to labeling, something more consequential than rhetorical laziness is occurring. Labels do not merely summarize disagreement; they reorder the conditions under which disagreement is allowed to exist. In MAGA discourse, terms such as Trump Derangement Syndrome, groomer, Marxist, woke mind virus, and enemy of the people function less as descriptions than as acts of exclusion. They do not answer arguments. They render the person making them unfit to be answered.

This process is best understood through the concept of delegitimization. Bar-Tal’s foundational work defines delegitimization as a psychological and social mechanism through which individuals or groups are pushed outside the boundaries of acceptable moral and epistemic standing. Once delegitimized, an opponent is no longer treated as a legitimate participant in shared reality. Their claims are not weighed, challenged, or corrected; they are dismissed as products of corruption, pathology, or malicious intent. Engagement becomes unnecessary because the speaker has already been disqualified (Bar-Tal, 1989; Bar-Tal, 1990).

Delegitimizing labels perform this exclusion efficiently. They collapse complex arguments into morally charged categories that require no further processing. Calling criticism “derangement” reframes political disagreement as mental instability. Calling educators “groomers” transforms policy disputes into accusations of moral contamination. Calling opponents “Marxists” or “enemies” shifts debate from substance to existential threat. The label substitutes for analysis, allowing dismissal to masquerade as diagnosis.

Van Dijk’s work on ideological discourse explains how this linguistic compression operates. Ideological language does not aim primarily to persuade across group boundaries; it aims to reinforce ingroup cohesion by controlling how reality is framed. Labels serve as cognitive shortcuts that signal who is credible and who is not, long before any claim is evaluated. Once such labels are internalized, they guide attention automatically. Information associated with delegitimized sources is filtered out not through conscious rejection, but through preemptive exclusion (van Dijk, 1998).

This is why delegitimization feels intuitive rather than calculated. Shortcut cognition reduces cognitive load by resolving ambiguity quickly. Instead of grappling with uncomfortable evidence or complex arguments, the mind reaches for a familiar category that settles the matter. The label does the work that reasoning would otherwise require. What is lost in this process is not simply nuance, but the very possibility of shared evaluation.

Lifton’s analysis of totalist language adds another layer to this dynamic. In closed ideological systems, language becomes morally saturated and emotionally loaded in ways that narrow the range of permissible thought. Words acquire absolute meanings that collapse description and judgment into a single gesture. Once this occurs, disagreement is no longer experienced as difference of interpretation. It is experienced as threat. The function of such language is not to clarify reality, but to defend the moral boundaries of the group against contamination (Lifton, 1961).

Within MAGA discourse, delegitimizing labels operate precisely in this totalist fashion. They do not merely criticize positions; they assign moral status to people. This is why accusations often escalate rapidly from policy disagreement to claims of corruption, perversion, or treason. The escalation is not accidental. It reflects a system in which legitimacy itself is at stake, and where preserving moral clarity requires drawing hard boundaries between the righteous and the irredeemable.

What makes this mechanism especially revealing is how it is mirrored back onto critics. MAGA routinely accuses the left of delegitimization, censorship, and moral absolutism, even as it relies on delegitimizing labels as a primary mode of discourse. This is not hypocrisy in the ordinary sense. It is displacement. The act of naming is projected outward and condemned in others to neutralize scrutiny of its use at home.

Here, the contrast provided by research on belief revision is instructive. Cohen, Aronson, and Steele showed that when individuals feel secure in their moral standing, they become more willing to evaluate evidence that challenges their views. Self-affirmation reduces defensiveness and increases openness to correction. The absence of such security produces the opposite effect: beliefs harden, and challenges are treated as threats rather than information (Cohen et al., 2000).

Delegitimization-by-label forecloses this corrective process entirely. By denying critics epistemic standing, it ensures that no amount of evidence can trigger revision. Arguments never reach the evaluative stage because the speaker is excluded before evaluation begins. The accusation that “the left does this too” then functions as moral laundering. If delegitimization is universal, it ceases to be a problem that requires restraint. If everyone is guilty, no one is accountable.

This is why labeling replaces analysis rather than supplementing it. Analysis invites uncertainty. Labels restore certainty instantly. They allow loyalty to remain intact without requiring engagement with facts that might strain it. In this sense, delegitimization is not merely a rhetorical habit; it is a psychological solution to the problem of accountability.

The result is a discourse in which mechanisms are recognized but never owned. MAGA accurately identifies the dangers of censorship, moral absolutism, and exclusion when these are attributed to outsiders. Yet the same behaviors, enacted through delegitimizing language at home, remain invisible. The accusation does not fail to describe reality. It fails to locate it correctly.

Delegitimization-by-label thus reveals the deeper pattern running through MAGA discourse. Awareness is present. Insight is not. The mirror works only when it faces outward.

V. “The Left Does It Too”: False Symmetry as Moral Laundering

When confronted with evidence of authoritarian behavior, MAGA’s most consistent response is not denial but diffusion. The claim is rarely that the behavior did not occur. It is that it is universal. Whatever abuse of power is named, whatever erosion of democratic norms is identified, the answer arrives quickly and predictably: the left does it too. From the inside, this feels like fairness. Structurally, it functions as something else entirely. It dissolves responsibility.

False symmetry operates by flattening distinction. Differences in scale, frequency, institutionalization, and consequence are collapsed into a single moral field where all actors are presumed equally compromised. Once that flattening occurs, no specific behavior requires correction. If everyone is guilty, no one is obligated to stop. Accountability survives only as a rhetorical gesture, not as a practical demand.

The psychological mechanics behind this move are well documented. Lord, Ross, and Lepper demonstrated that individuals exposed to conflicting political evidence do not neutrally weigh that evidence. They assimilate it selectively, crediting information that supports prior commitments while subjecting disconfirming information to heightened skepticism. The result is not moderation but polarization. Evidence that suggests asymmetry is not ignored; it is actively reframed so that symmetry can be preserved (Lord et al., 1979).

Group influence intensifies this process. Cohen’s research showed that individuals routinely subordinate policy preferences to group alignment, even when doing so contradicts previously stated beliefs. What matters is not coherence with evidence but coherence with identity. Under these conditions, acknowledging that one’s own side engages in more systematic democratic violations than its opponent is not merely an empirical judgment. It is a threat to group membership. False symmetry resolves that threat by preserving loyalty while appearing even-handed (Cohen, 2003).

Motivated reasoning explains why this resolution feels honest rather than evasive. Kahan’s work on identity-protective cognition shows that individuals reason toward conclusions that protect their standing within valued groups. This process is experienced subjectively as objectivity. Claims of balance allow individuals to maintain a self-image organized around fairness without confronting evidence that would require moral recalibration. The assertion that “both sides do it” relieves dissonance by erasing distinctions that would otherwise demand action (Kahan et al., 2007).

What disappears in this erasure is proportional judgment. Asymmetry blindness emerges when differences in magnitude and intent are treated as irrelevant. An isolated overreach is equated with a coordinated campaign. A rhetorical excess is equated with institutionalized policy. Once these distinctions collapse, evaluation becomes impossible. Everything is bad, therefore nothing is urgent.

Social dominance theory provides context for why this collapse is tolerable. Sidanius and colleagues describe how individuals comfortable with hierarchical social arrangements are more willing to diffuse moral responsibility when dominance is challenged. Harm directed outward becomes easier to justify when it is framed as reciprocal or inevitable. False symmetry normalizes misconduct by embedding it in a story of perpetual mutual aggression, rather than isolating it as a problem requiring restraint (Sidanius et al., 2004).

What makes this maneuver especially effective is its modesty. It does not demand that any specific act be defended. It demands only that no act be treated as uniquely disqualifying. The conversation shifts away from what happened and toward whether anyone has clean hands. In that shift, scrutiny evaporates.

This is why “both sides” rhetoric persists even when evidence is uneven. It is not a failure of comparison. It is a refusal of consequence. False symmetry preserves the language of moral standards while stripping them of force. It acknowledges authoritarian mechanisms in theory while ensuring they never require intervention in practice.

The result is a political posture in which awareness survives without obligation. Mechanisms are named, condemned, and displaced, all without ever being owned. What appears as balance functions as insulation. Loyalty remains intact, and principle is preserved only as an abstraction.

VI. Real-World Projection in Action: Where the Accusations and Behaviors Invert

The claim that projection animates MAGA discourse is not a speculative psychological inference. It is empirically observable. Across multiple domains of public life, MAGA-aligned actors accuse political opponents of behaviors that closely mirror their own actions. The pattern is not subtle. It is repeated, well documented, and consistent across policy areas. What varies is not the mechanism, but the target.

Consider censorship and so-called cancel culture. MAGA rhetoric regularly frames the left as uniquely hostile to free speech, accusing liberals, educators, and technology platforms of suppressing dissenting views. These claims are typically advanced in response to private companies enforcing content rules or institutions choosing not to platform certain speakers. At the same time, MAGA-led state governments have enacted some of the most expansive content restrictions in modern U.S. history. Laws restricting classroom discussion of race, gender, and sexuality, mass removal of books from public schools and libraries, and direct state intervention in curricula have all been justified as defenses against “woke indoctrination.” The behavior being condemned when attributed to the left is reframed as protection when enacted by the right. The mechanism is identical. Only the moral framing changes.

A similar inversion appears in accusations of authoritarianism. MAGA figures routinely describe Democratic leadership as dictatorial, often framing routine law enforcement or judicial processes as political persecution. These accusations intensified in response to investigations and indictments involving Donald Trump, which were portrayed as evidence of tyranny rather than of institutional accountability. Yet the same movement largely excused, minimized, or justified Trump’s own attempts to overturn the 2020 election, his pressure campaigns against state officials, his efforts to submit false slates of electors, and his encouragement of actions that disrupted the peaceful transfer of power. When authority is exercised through established legal channels against MAGA leaders, it is labeled authoritarian. When authority is wielded personally, extralegally, or coercively by MAGA leaders themselves, it is framed as necessary resistance.

The pattern repeats in claims about weaponizing government. MAGA discourse frequently alleges that federal agencies have been turned into partisan instruments targeting conservatives. Investigations, audits, and prosecutions are described as evidence of a corrupt “deep state.” At the same time, extensive reporting documents Trump’s repeated efforts to direct the Department of Justice against political opponents, to interfere in cases involving his allies, and to demand personal loyalty from law enforcement institutions. These actions are not speculative. They were recorded, investigated, and, in some cases, resisted by career officials. Yet when MAGA actors engage in or attempt overt politicization of law enforcement, it is rationalized as correction or cleanup, while comparable actions directed at them are framed as abuse.

Nowhere is the inversion more consequential than in claims of election fraud. MAGA’s defining narrative since 2020 has been that Democrats systematically rig elections, despite the absence of evidence supporting those claims. Courts rejected dozens of lawsuits. State officials, including Republicans, affirmed the integrity of the vote. Nonetheless, the accusation persisted. Simultaneously, Trump and his allies engaged in actions that constitute direct attempts to alter certified results: pressuring election officials, promoting fabricated elector slates, and inciting efforts to halt certification. The accusation of fraud did not merely precede these actions; it functioned as their justification. By projecting fraud outward, MAGA normalized behavior that would otherwise be recognized as election subversion.

Accusations of indoctrinating children follow the same structure. MAGA rhetoric depicts educators, librarians, and LGBTQ advocates as engaged in coordinated efforts to corrupt or “groom” children. These claims rely on moral panic rather than evidence. In response, MAGA-aligned governments have imposed ideologically prescriptive curricula, restricted historical and social content, and sanctioned teachers for deviation from state-approved narratives. Initiatives framed as defending children from indoctrination have resulted in state-mandated ideological instruction. Again, the behavior condemned in others is enacted directly, but renamed.

Across these domains, the inversion is consistent. MAGA identifies real democratic dangers—censorship, authoritarianism, politicized institutions, election manipulation, ideological coercion. The recognition is often accurate at the level of structure. What is displaced is agency. The behaviors are acknowledged only when attributed to an outgroup, and denied or reframed when enacted by the ingroup.

This is why these accusations resonate. They are not fabrications. They are misassignments. The structure is recognized, then projected outward. The accusation does not fail because it misunderstands authoritarian mechanisms. It fails because it refuses self-application.

The empirical record makes this difficult to dismiss as mere opinion. Across independent reporting from major news organizations, the same pattern emerges repeatedly. The claim that “the left does it” functions less as comparative analysis than as psychological insulation. It neutralizes critique by converting accountability into reciprocity. If everyone is guilty, then no one is obligated to stop.

What this section demonstrates is not moral hypocrisy, but psychological consistency. The accusations are coherent. The behavior is observable. The inversion is the point.

VII. Collective Narcissism and Moral Immunity: Why MAGA Must See Itself as Righteous

If loyalty is the organizing value and projection is the defense that protects it, collective narcissism is the emotional architecture that makes the system feel justified. Collective narcissism describes a form of group identification in which members believe their group is uniquely virtuous, exceptional, and deserving of recognition, while simultaneously feeling chronically unappreciated and persecuted. This combination is psychologically volatile. It produces a worldview in which the group is always right and always wronged.

Golec de Zavala’s research shows that collective narcissism is not simply strong group pride. It is contingent self-esteem projected onto the group. Because the group’s moral worth feels fragile and externally threatened, criticism is experienced not as disagreement but as humiliation. Any challenge to the group’s conduct becomes an attack on its identity. Under these conditions, accountability does not feel corrective. It feels abusive (Golec de Zavala et al., 2020).

This dynamic explains why MAGA supporters can experience themselves as victims even while exercising disproportionate political power. Collective narcissism allows dominance and grievance to coexist without contradiction. Power is interpreted as rightful restoration, while resistance to that power is framed as persecution. The group does not see itself as imposing its will; it sees itself as reclaiming what was unjustly denied.

The concept of “authoritarians as revolutionaries in reverse” captures this paradox. Rather than seeking radical transformation, such movements aim to restore a mythologized moral order in which their dominance was unquestioned. Any deviation from that order is experienced as illegitimate, and any opposition to its restoration is cast as tyranny. The group’s actions are therefore always defensive, even when they are coercive.

Social dominance theory provides structural reinforcement for this psychology. Sidanius and Pratto show that groups comfortable with hierarchy are more likely to rationalize inequality and exclusion, especially when dominance feels threatened. When combined with collective narcissism, this comfort with hierarchy produces moral immunity. Harm inflicted on outgroups does not register as harm, because those groups are no longer perceived as deserving equal moral consideration (Sidanius & Pratto).

Carter and Murphy’s work on moral exclusion clarifies how this immunity operates. Moral concern is not distributed evenly. It is conditional. Groups perceived as illegitimate, disloyal, or contaminating are placed outside the circle of moral obligation. Once excluded, they can be censored, punished, or erased without triggering moral conflict. Actions that would otherwise provoke ethical restraint are reclassified as necessary defenses of the righteous group.

This is the final piece that explains why projection is not only persistent but emotionally satisfying. Collective narcissism ensures that the group’s self-image remains intact regardless of evidence. Projection preserves that image by relocating wrongdoing elsewhere. False symmetry then diffuses responsibility, and delegitimizing labels prevent scrutiny from reentering the system.

The result is moral immunity. MAGA can believe itself both besieged and blameless, persecuted and justified, without experiencing contradiction. Criticism becomes proof of hostility. Accountability becomes oppression. Power becomes virtue.

This is why awareness alone changes nothing. The mechanisms are visible. The structures are named. But self-recognition would require relinquishing moral innocence, and collective narcissism cannot tolerate that loss. Righteousness is not merely believed; it is required.

The system holds because it must.

VIII. Why the Mirror Cannot Turn Inward: The Cost of Self-Recognition

The final barrier to self-recognition in authoritarian movements is not informational. It is moral. Turning the mirror inward would require conceding that harm has been done in the group’s name, that leaders are capable of serious wrongdoing, and that loyalty may at times conflict with principle. Authoritarian psychology forbids all three, not because they are unthinkable in the abstract, but because they threaten the structure that holds identity together.

Altemeyer’s later work makes this constraint explicit. Authoritarian followers do not merely prefer strong leaders; they experience those leaders as embodiments of moral order. Questioning them is not interpreted as accountability but as subversion. When authority is perceived as legitimate, submission becomes a virtue and dissent becomes a vice. Under these conditions, admitting moral error by the ingroup would fracture the chain that connects obedience to righteousness. The cost of such an admission is not embarrassment. It is disorientation (Altemeyer, 1996; Altemeyer, 2020).

Lifton’s analysis of totalist systems clarifies why this disorientation is so dangerous. Totalist environments do not tolerate ambiguity well. They rely on moral certainty, bounded language, and clear divisions between good and evil to maintain coherence. Self-recognition introduces ambiguity at precisely the wrong point. It collapses the distinction between defender and threat. Once the group is capable of wrongdoing, the moral universe becomes unstable. Projection resolves that instability by exporting error outward, preserving the internal narrative intact (Lifton, 1961).

Stenner’s work adds an important conditional insight. Authoritarian tendencies intensify under perceived threat, particularly threats to normative order and group unity. In such moments, tolerance for dissent declines and the demand for conformity rises. Self-critique, which might otherwise be survivable, becomes intolerable. The group does not interpret reflection as maturity. It interprets it as weakness. Choosing principle over loyalty feels less like integrity than like surrender (Stenner, 2005).

Dean and Altemeyer’s analysis of Trump’s support base underscores how these dynamics operate in practice. They document how evidence that would ordinarily prompt reassessment instead triggers defensive consolidation. Facts are not rejected because they are implausible, but because accepting them would require revising the moral status of the leader and, by extension, the follower. Once identity is fused with authority, accountability becomes existentially threatening (Dean & Altemeyer, 2020).

This is why intelligence, education, and exposure to information fail to break the pattern. The barrier is not cognitive. It is structural. Self-recognition would require dismantling the moral architecture that renders loyalty meaningful. It would require acknowledging that obedience can coexist with wrongdoing, that authority can be illegitimate, and that righteousness is not guaranteed by affiliation. For authoritarian identities, these acknowledgments are not merely uncomfortable. They are disallowed.

The mirror cannot turn inward because doing so would collapse the distinction between protector and perpetrator on which the worldview depends. Projection preserves that distinction. Delegitimization enforces it. False symmetry diffuses responsibility for it. Together, they form a closed system that maintains certainty by preventing self-application.

What appears from the outside as denial is, from the inside, preservation. Awareness exists. Insight is prohibited. The system holds not because it is blind, but because seeing clearly would cost too much.

IX. Conclusion: Awareness Without Permission

By this point, the pattern is no longer theoretical. The research converges on a simple but unsettling conclusion: MAGA’s failure is not one of perception, but of application. The mechanisms are recognized with striking clarity when they can be assigned to an outgroup. Delegitimization, censorship, indoctrination, authoritarianism, and abuse of power are all named accurately, often in language that mirrors academic descriptions. What is missing is not awareness of structure, but permission to locate that structure within the self or the group.

Psychological research offers a consistent explanation for this asymmetry. Identity-protective cognition prioritizes the preservation of group belonging and moral self-image over accuracy. Once loyalty becomes the organizing value, evidence is filtered not by its correspondence to reality but by its implications for identity. Projection resolves the resulting tension by allowing individuals to discharge guilt and threat outward while maintaining internal coherence. False symmetry then completes the circuit, laundering responsibility by dissolving distinctions between initiator and responder, power-holder and critic, perpetrator and target (Kahan et al., 2007; Lord et al., 1979; Cohen, 2003).

Authoritarian psychology sharpens this dynamic further. Submission to perceived legitimate authority, moral absolutism, and intolerance of ambiguity render self-critique destabilizing rather than corrective. In such systems, reflection is reframed as betrayal, and accountability as persecution. The group’s moral narrative depends on the assumption of righteousness, and any inward application of critique threatens to fracture that narrative at its foundation (Altemeyer, 1996; Stenner, 2005; Lifton, 1961). What looks from the outside like denial or bad faith is, from the inside, an act of psychological preservation.

This is why the accusations persist even when contradicted by evidence, and why they often sound uncannily precise. They are precise. They are simply displaced. MAGA does not lack awareness. It lacks permission to apply awareness inward. That absence is not accidental or incidental. It is the load-bearing feature of an identity organized around loyalty, grievance, and moral certainty. Until that structure changes, insight will remain dangerous, mirrors will remain outward-facing, and recognition will continue without self-recognition.

References

Adorno, T. W., Frenkel-Brunswik, E., Levinson, D. J., & Sanford, R. N. (1950). The authoritarian personality. New York: Harper & Brothers.

Altemeyer, B. (1996). The authoritarian specter. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Altemeyer, B. (2020). Authoritarian nightmare: Trump and his followers. Brooklyn, NY: Melville House.

Dean, J. W., & Altemeyer, B. (2020). Authoritarian nightmare: Trump and his followers. Brooklyn, NY: Melville House.

Hetherington, M. J., & Weiler, J. D. (2009). Authoritarianism and polarization in American politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lifton, R. J. (1961). Thought reform and the psychology of totalism. New York: W. W. Norton.

Sidanius, J., & Pratto, F. (2001). Social dominance: An intergroup theory of social hierarchy and oppression. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Stenner, K. (2005). The authoritarian dynamic. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

van Dijk, T. A. (1998). Ideology: A multidisciplinary approach. London: Sage.

Bar-Tal, D. (1989). Delegitimization: The extreme case of stereotyping and prejudice. In D. Bar-Tal, C. F. Graumann, A. W. Kruglanski, & W. Stroebe (Eds.), Stereotyping and prejudice: Changing conceptions (pp. 169–182). New York: Springer.

Bar-Tal, D. (1990). Causes and consequences of delegitimization: Models of conflict and ethnocentrism. Journal of Social Issues, 46(1), 65–81.

Carter, E. R., & Murphy, M. C. (2015). Group-based differences in moral exclusion. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 41(8), 1120–1136.

Cohen, G. L. (2003). Party over policy: The dominating impact of group influence on political beliefs. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(5), 808–822.

Cohen, G. L., Aronson, J., & Steele, C. M. (2000). When beliefs yield to evidence: Reducing biased evaluation by affirming the self. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 26(9), 1151–1164.

Golec de Zavala, A., Cichocka, A., Eidelson, R., & Jayawickreme, N. (2009). Collective narcissism and its social consequences. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 97(6), 1074–1096.

Jones, E. E., & Nisbett, R. E. (1971). The actor and the observer: Divergent perceptions of the causes of behavior. In E. E. Jones et al. (Eds.), Attribution: Perceiving the causes of behavior. Morristown, NJ: General Learning Press.

Kahan, D. M., Braman, D., Gastil, J., Slovic, P., & Mertz, C. K. (2007). Culture and identity-protective cognition: Explaining the white-male effect in risk perception. Journal of Empirical Legal Studies, 4(3), 465–505.

Lord, C. G., Ross, L., & Lepper, M. R. (1979). Biased assimilation and attitude polarization: The effects of prior theories on subsequently considered evidence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37(11), 2098–2109.

Pronin, E., Lin, D. Y., & Ross, L. (2002). The bias blind spot: Perceptions of bias in self versus others. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28(3), 369–381.

Sidanius, J., Pratto, F., van Laar, C., & Levin, S. (2004). Social dominance theory: Its agenda and method. Political Psychology, 25(6), 845–880.

Golec de Zavala, A. (2020). Authoritarians and “revolutionaries in reverse”: Why collective narcissism threatens democracy. Political Psychology.

Associated Press. Fox News says it ‘addressed’ onscreen message that called Biden a ‘wannabe dictator’. - https://apnews.com/article/fox-wannabe-dictator-biden-trump-speech-1a9750c5dfcfb0a6482f3c51674ae08f

Associated Press. Trump wants to end ‘wokeness’ in education. He has vowed to use federal money as leverage

NPR. GOP candidates and leaders subpoenaed as Jan. 6 panel dives into fake electors scheme

Reuters. In Recorded Call Trump Pressures Georgia Official to Find Votes to Overturn the Election - https://www.reuters.com/world/us/recorded-call-trump-pressures-georgia-official-change-election-results-media-2021-01-03/

Reuters. Florida introduces new guidelines on teaching Black history, critics give poor grade

Goodness! Maybe it’s safest to just stay in bed….

What frightens me the most is how close to the brink we are to another mass atrocity. People immediately shut down when comparisons are made to Nazi Germany. Mass deportation is not equivalent to mass extinction, people say. Except, German officials didn’t start a fascist campaign of extermination. Jews were first dehumanized, othered, blamed for Germany’s financial problems and moral “rot.” Today, read any MAGA comment on social media, and they echo Trump’s hateful rhetoric. Immigrants are criminals, and they are “poisoning the blood” of America.

Next, came laws that stripped Jews of property rights, employment opportunities, and forbid inter-marriage. The reasoning? Germany didn’t belong to them. Trump regime is firing immigration judges, and deporting people without regard to their constitutional rights. He signs executive orders that are in violation of the constitution, smears federal judges as “rogue” (his own, as RINOs), lies to courts routinely, and ignores court orders flagrantly.

Then came mass deportation of Jews. That didn’t work out so well for the Nazis. Too many Jews, too few countries willing to accept them (including the US). Then they were rounded up and forced into Ghettos. Today, we are building detention centers in swamplands, converting warehouses to hold humans, tossing people into tent cities that do not keep elements out and ensure widespread illness and disease.

The “final solution” of forced labor camps, turned into extermination of prisoners, did not come about until nearly 5 years into Hitler’s expansionist war - 1942. One year after Hitler declared war on the United States, and Japan bombed Pearl Harbor.

We are not mass exterminating immigrants - yet. We are sending many to near certain death. 3rd country deportations, whereby we understand that the 3rd countries will simply deport immigrants right back to their countries of origin - places our federal judges forbid detainees to be deported to. Trump is stripping people of their lawful statuses - getting rid of TPR, ordering “deportation judges” (this is what DHS is now calling them) to drop asylum claims without hearing cases. We are deporting people back to places they fled from, with well-founded UN documented fear of persecution, torture, death.

Yet. We are not exterminating people with forceful intention. Yet.

Your article confirms that we can all be monsters.